The Tar: A Cultural Icon and a Musician’s Companion

Introduction

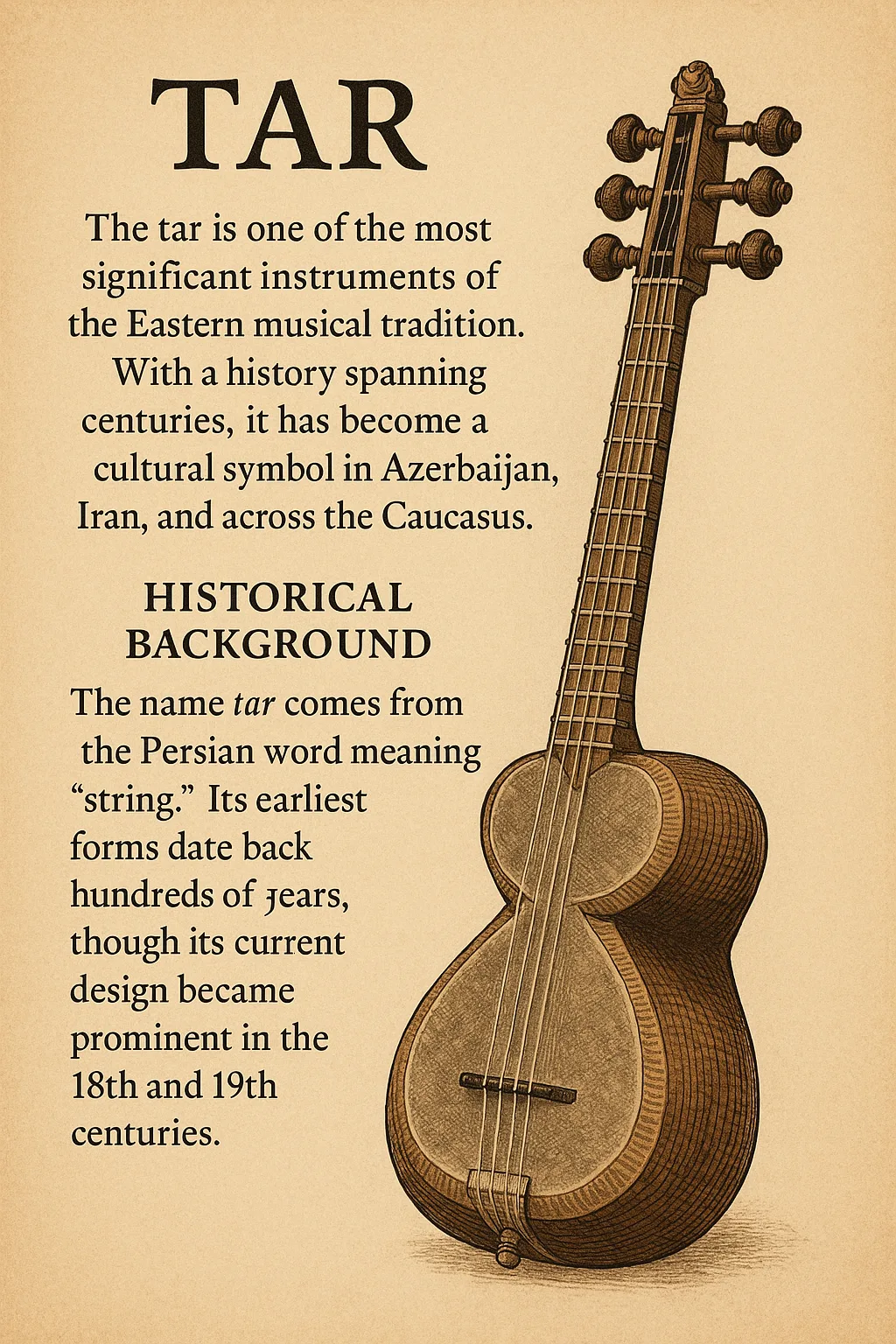

The tar is one of the most celebrated stringed instruments of the Eastern world, renowned for its expressive range, distinctive timbre, and deep cultural roots. Originating across Iran, Azerbaijan, and the Caucasus, it functions both as a vessel of heritage and a versatile companion for modern performers. Today, the tar stands at the crossroads of tradition and innovation, inviting ethnomusicologists, composers, and students to explore its singular voice.

Historical and Cultural Significance

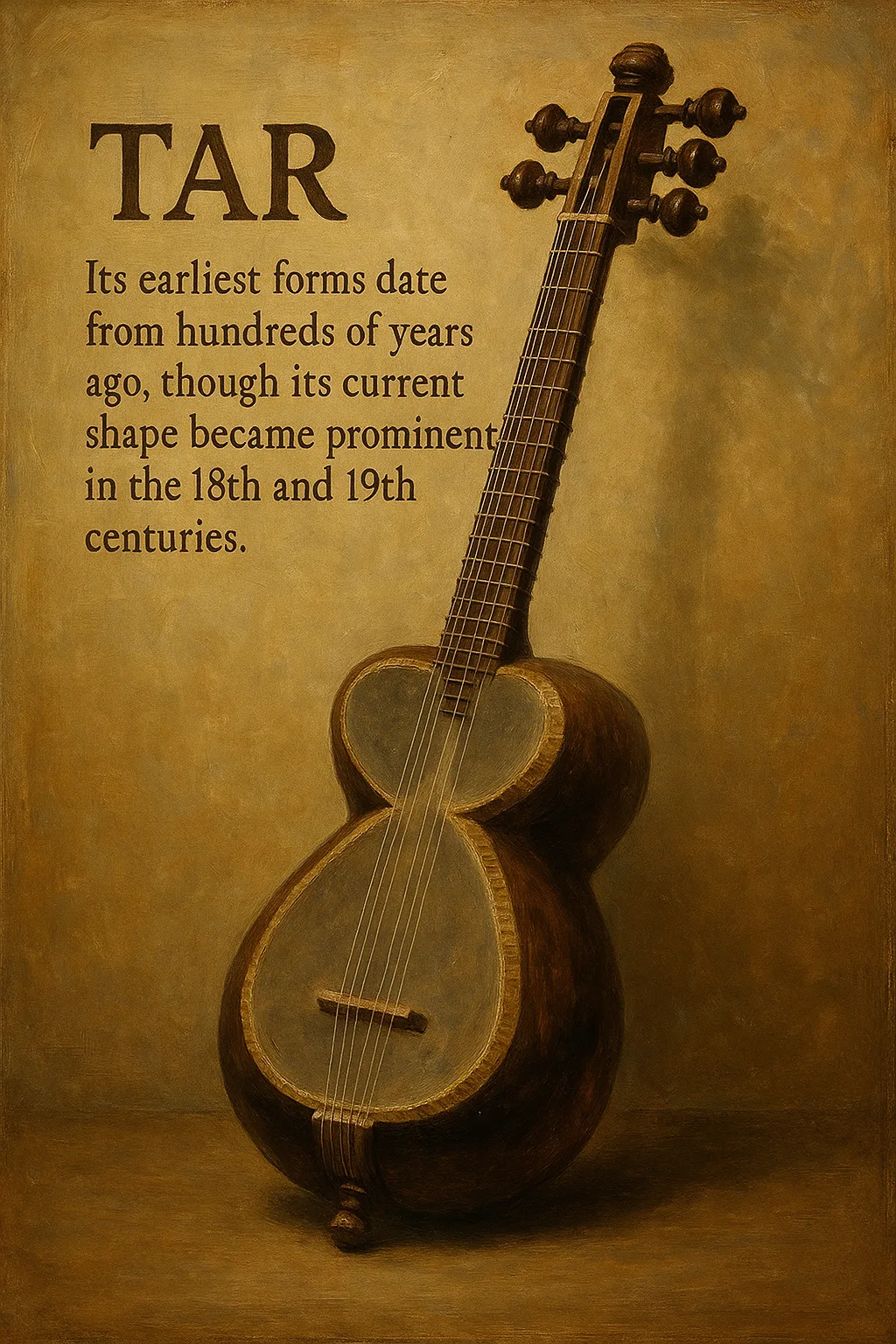

The word tar means “string” in Persian. Although antecedents stretch back centuries, the instrument’s modern form crystallized in the 18th–19th centuries, when Azerbaijani innovators—most notably Sadigjan—expanded its stringing and refined its proportions for greater projection and agility. In Azerbaijan, the tar is a symbol of national identity and a central voice in mugham; in Iran, it is a cornerstone of the radif and dastgāh tradition. The instrument’s cultural stature has also been recognized internationally through heritage listings and widespread concert performance.

Instrument Anatomy: How Design Shapes Sound

Body & Membrane

The tar’s instantly recognizable double-bowl (figure-eight) body is typically carved from mulberry and capped with a taut lamb or goat skin. A floating bridge concentrates energy into the membrane, creating the tar’s quick attack, articulate presence, and singing sustain.

Neck, Frets, and Setup

The neck is often w walnut or another stable hardwood. Movable frets, tied from gut or modern synthetics, unlock microtonal nuance essential to dastgāh and mugham. Teachers frequently retie fret positions to suit a student’s hand and repertoire. A moderate action—around 2.5–3.0 mm at mid-neck—is a versatile starting point for clarity and speed.

Strings and Plectrum

Persian instruments commonly use six strings in three courses, while Azerbaijani models often extend to ~11 strings (adding drones and sympathetic strings). The index-mounted ring plectrum (mezrāb/zakhmeh) enables rapid tremolo (riz), incisive accents, and delicate brushed textures.

Persian and Azerbaijani Variants: A Side-by-Side View

| Feature | Persian Tar | Azerbaijani Tar | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body | Double-bowl mulberry | Similar double-bowl; often slightly larger/deeper | Both use a floating bridge on skin |

| Soundboard | Thin lamb/goat membrane | Membrane under slightly tighter tension | Quick attack, bright edge |

| Scale length | ~650–680 mm | ~670–700 mm | Varies by maker and repertoire |

| Frets | Movable; ~22–28 total | Movable; ~24–28 total | Microtonal intervals set by hand |

| Strings | 6 (3 courses) | ~11 (melody + drones/resonance) | Extra strings add shimmer & projection |

| Common tunings | C–G–C or D–A–D | Central course often a 4th/5th above bass | Adjusted per dastgāh/mugham |

| Primary traditions | Iranian dastgāh / radif | Azerbaijani mugham | Improvisation is core in both |

Tuning, Range, and Core Techniques

There is no single “standard” tuning because the tar serves modal systems. Many Persian players favor C–G–C or D–A–D on the three principal courses (unison or octave pairs), while Azerbaijani setups vary with the mugham and allocate additional strings to drones and resonance. Expect a practical range just over two octaves, expanded by position shifts and ornaments.

- Riz (tremolo): A fast, even flutter with the ring plectrum that creates singing sustain.

- Hammer-ons & pull-offs: For fluid, vocal phrasing within modal steps.

- Slides (glissando) & vibrato: Controlled micro-shifts coloring pitches to each mode’s character.

- Cross-string ornaments: Alternating adjacent courses to articulate contrast between stable and tension tones.

Learning Path: From First Notes to Improvisation

Beginners typically start with posture, right-hand control for riz, and near-diatonic fret layouts before moving into microtonal practice. Because frets are movable, ear training is essential: students learn to hear and place characteristic intervals for each dastgāh or mugham. Traditional apprenticeship remains a powerful route, but conservatories and online materials now provide structured paths for international learners.

Buying Guide: What to Check

- Wood & build: Clean joins, no hairline cracks at the bowls or neck heel; light yet resilient body.

- Membrane: Even thickness and firm, wrinkle-free seating. Over-slack skins buzz; over-tight skins choke.

- Frets: Firmly tied with neat knots (usually bass side), no sharp ends; spacing consistent with your school.

- Neck relief & action: Slight relief is fine; avoid twist. Aim around 2.5–3.0 mm action at mid-neck.

- Balance: Seated posture should feel natural; on Azerbaijani tars held across the chest, ensure the headstock doesn’t dive.

- Hardware & strings: Smooth pegs (wood or geared). Replace old strings to hear the instrument’s true voice.

- Teacher alignment: Ask a local master which makers match your repertoire and technique goals.

Care & Maintenance

Skin-topped instruments are climate sensitive. Keep relative humidity around 40–55%. In dry seasons, use a case humidifier to prevent shrinkage and buzz; in humid weather, avoid direct sun or heat that can slacken the skin. Wipe strings after playing and change them when brightness fades or intonation drifts. If the membrane loosens or tears, consult a specialist—re-skinning dramatically affects tone.

Recording & Amplification Tips

- Microphone placement: A small-diaphragm condenser 20–30 cm off the bridge area captures attack without harshness; angle slightly toward the upper bowl for body.

- Stage volume: Contact pickups on the bridge or rim can work; pair with a preamp, a gentle high-shelf, and a narrow notch to tame resonant peaks.

- Blend strategy: When possible, blend roughly 70% mic / 30% pickup for a natural yet controllable sound.

Notable Artists and Repertoire

Azerbaijani masters such as Bahram Mansurov and Ramiz Guliyev brought the instrument to global stages, while Iranian virtuosos like Ali-Akbar Shahnazi preserved and expanded classical technique and repertoire. Their recordings serve as living textbooks for tone production, phrasing, and modal interpretation.

Modern Ensembles and Cross-Genre Collaborations

Beyond classical contexts, the tar thrives in national orchestras, chamber groups with kamancheh and daf, and cross-genre projects. Contemporary composers and improvisers increasingly fold the tar into jazz, fusion, and world-music settings, where its bright articulation and microtonal color add striking textures.

The tar is both a cultural icon and a musician’s companion. Its design—a resonant double-bowl body, skin soundboard, floating bridge, and movable frets—enables a voice that is at once crisp and lyrical, ancient and modern. Whether you are drawn to the meditative arcs of dastgāh or the high-energy climaxes of mugham, the tar rewards attentive ears and daily practice. With thoughtful setup, mindful care, and guidance from tradition, this elegant long-necked lute will speak in a voice unmistakably your own.